For a few minutes on Saturday twitter was abuzz tracking the Eastern Michigan-Northern Illinois game. The only way a low-end MAC game has mass-appeal is if something extremely unusual happens, and in this case it was NIU’s four-point half that got people’s attention. The Huskies’ struggles continued to a lesser extent into the second half, and at one point they were 0-for-32 on three-point attempts. Sadly, Daveon Balls was successful on NIU’s final three-ball, keeping the Huskies from establishing a record for three-point futility that may have stood for a long time.

When it was all over, there was something to be learned, though. More than just NIU’s offense is a disgrace to basketball. Hidden in the details of the circus-act of a game was that Rob Murphy’s defense probably has some control over its opponents’ three-point percentage.

As you know, I’m a believer that defenses have little control over opponents’ three-point percentage. Last season, when I first posted about this, the most obvious counter-arguments were Arizona and Drexel, both of whom were working on consecutive seasons in the top ten of 3P% defense. This season, Arizona ranks 263rd and Drexel ranks 165th. (That said, Sean Miller’s track record suggests his defenses have some influence on opponents’ 3P%.)

To say that the defense has little control over defensive 3P% is probably not the most precise way to put it. If a defense stopped guarding the three-point line or decided to never contest a shot, they would surely see their numbers suffer. (Though, Chattanooga seems to employ this strategy every season, and their defensive 3P% numbers are not quite horrible.)

To illustrate why a team might have little control over its opponents’ three-point shooting, consider a ball screen situation. If a defender goes under a ball screen, the ballhander, assuming he’s a good shooter, will be inclined to shoot. If the defender goes over the screen, the ballhandler’s response will not be to shoot a more difficult shot, it will be to not shoot at all. In this way, defensive strategies tend to impact the number of threes taken and not the percentage of threes made. By the end of the season, opponents have taken a mix of open and contested shots based on their own decisions, and from the defense’s point of view the distribution of these decisions isn’t going to differ much from team to team. Thus, the resulting rankings of defensive 3P% are largely random, influenced some by opponents shooting ability.

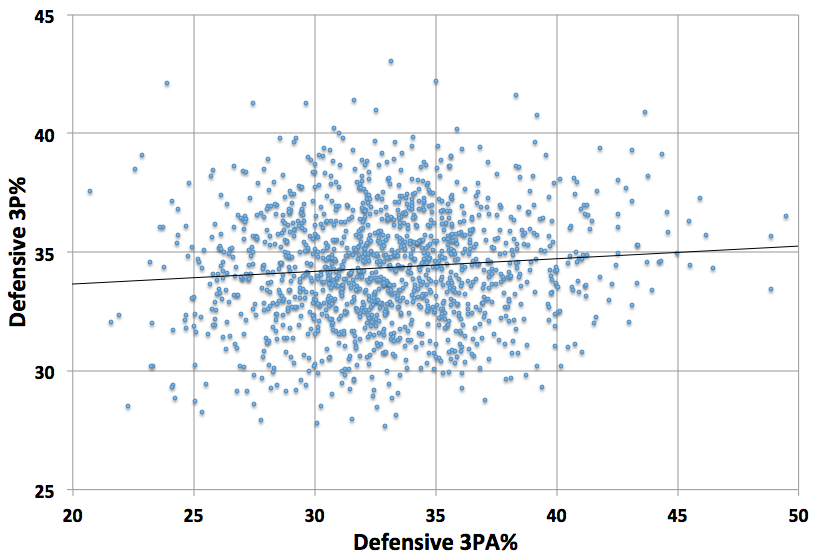

There is also very little relationship between defensive 3PA% vs. 3P%, which should give one pause that limiting attempts has any influence on the quality of shots being taken by an opponent. The following is a plot of season-long 3PA% defense against 3P% defense for all D-I teams over the past four seasons. (That’s 1,381 data points.)

There actually is a very slight trend for teams allowing more three-point attempts to give up a higher percentage of makes, but over the entire range of 3PA% defense, that difference in the trend of 3P% defense is just 1.5%. For every 1% decrease in 3PA%, defensive 3P% decreases by 0.05% on average. It’s a tiny trend that is completely swamped by the noise.

At this point, if you still want to put up a fight about the issue, you’re best approach is to point to Syracuse. The Orange are working on their fifth-consecutive season in the top fifty of defensive 3P%, and they also had consecutive top ten seasons in 2003 and 2004. If someone wanted to bet me that Syracuse would be in the top 50 in defensive 3P% next season, I wouldn’t bet against you because they probably will. Getting back to Rob Murphy, Boeheim’s former assistant who runs the exact same defense, he’s had some success keeping opponents’ 3P% low, as well. Last season EMU ranked 61th and so far this season, they’re 18th. That’s 13 seasons of Syracuse zone with 3P% defense success that’s difficult to ignore. And in all cases, these defenses are giving up tons of attempts.

Even in these cases, while it’s apparent that this style of defense has some control over opponents’ three-point percentage, I’d propose that control is largely indirect. One might say that Syracuse’s length bothers shooters more than other teams. I can offer two contradictory pieces of evidence to that. First, I have height data by position for every team. I’ve tried to construct a model that would predict defensive three-point percentage based on the size difference between a defense and its opponents, but I haven’t been successful. I mean, I haven’t even got close to success.

The other thing is that from a logical perspective, if you’re a 6’ 3” shooter and there’s a 6’ 7” guy responsible for guarding you, don’t you react to this situation pretty quickly? After getting your first shot contested, I would think you might be a little more cautious about shooting. Certainly after two contested shots, one would alter their behavior.

Now, maybe there are initially two or three shots like this in a game and that’s enough to influence Syracuse’s statistics in their favor. But I think the reason has more to do with the offense realizing that getting the ball to the rim against the lengthy 2-3 zone is not nearly as profitable as it is against most teams. Thus, they lower their standard for what a good three-point shot is. A player may take that open 25-footer that his coach would normally strangle him for because that’s a better shot than driving into the paint and getting swallowed up by trees.

While I believe the Boeheim 2-3 zone influences opponents’ three-point percentage, I don’t want to go overboard. They have a couple of systematic advantages that help their numbers. First, their non-conference schedule is largely home games and second, the Big East does not contain a lot of good perimeter-shooting teams. We can remove these two effects by looking at how the Orange have ranked in Big East play in conference games only.

Since 2004, here’s how those rankings looked: 1, 7, 15, 8, 4, 2, 4, 9, and 4. The Orange may have the league’s best 3P% defense, as much as such a thing exists, but it’s really difficult to see that consistently displayed over an 18-game stretch. Compare that to the Big East’s best two-point percentage defense over that time.

Here’s how UConn has ranked in the Big East in that category over the same nine-year stretch: 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 6, and 3. You just can’t dominate three-point percentage defense like that because there is so much variance involved from game-to-game, which I would say is due to the defense’s lack of influence on three-point percentage. (It’s true that there are fewer three-point attempts than two-point attempts which contributes to increased variance, but even accounting for this, two-point defense is more consistent than three-point defense from year-to-year.)

If you look at Syracuse’s 17 NCAA tournament games since 2004, opponents have made 32.8% of their threes, about 2% below the national average over that time. I don’t have any fancy math to prove this, but I would guess that’s about the influence of the Boeheim zone on opponents shooting: somewhere around 2 to 3%. A 40% team would be expected to shoot 37% against Syracuse or Eastern Michigan.

In other words, you’d be better off assuming teams have no control over three-point defense than assuming swings over a two or three game stretch say anything about one’s defense. I’m willing to concede the Boeheim zone has some influence, but it’s small. And I remain convinced that Ray Giacoletti had it completely backwards. If you want to keep opponents from making three-point shots, your best move is to prevent them from taking those shots.