If it’s the middle of summer and you’re obsessing about trends in offensive rebounding, then you’re either me or some sort of lunatic. I was initially concerned about a very specific aspect of offensive rebounding for an upcoming feature, but along the way I decided to look at the different things related to offensive rebounding that one can mine from play-by-play data, and that led me to what you are about to see.

This isn’t going to be the most glamorous piece of analysis, but if there was a good time for an offensive rebounding data dump, this is it. Now for some facts regarding those second chances…

1. The offensive rebound is dying.

Every single season since 2007, the chances of a missed shot being rebounded by the offense has decreased as stopping transition is prioritized at the expense of getting second chances. If you listen to enough coaches, it doesn’t take long to understand that this is the prevailing thinking, though it may be a bit misguided. You still have Jamie Dixon, Rick Barnes, Tom Moore, and Pat Skerry out there holding the line on attacking the glass, but their ranks decrease with each passing season.

D-I offensive rebounding percentage

Season OR% 2006 34.0 2007 33.5 2008 32.872 2009 32.871 2010 32.7 2011 32.3 2012 32.1 2013 31.8 2014 31.4

This piece isn’t intended to bemoan the demise of offensive rebounds. I’d like to see more of it because it makes the game more interesting, but I’d also like to see 80-possession games more regularly and that’s not going to happen anytime soon. I’ll watch regardless.

2. The offensive rebound of a missed free throw is really dying.

It turns out that while offensive rebounding percentage is falling for every shot type listed in the play-by-play, last season saw a sharp decline in offensive rebounds of missed free throws.

Free throws 2-point jumpers 3-pointers Layups, etc. Year OR-DR OR% OR-DR OR% OR-DR OR% OR-DR OR% 2010 6290-33953 15.6 43645-86143 33.6 39336-86424 31.3 32861-45147 42.1 2011 5975-33525 15.1 42430-86215 33.0 38717-87024 30.8 32409-44492 42.1 2012 5638-32677 14.7 41063-84242 32.8 38506-87146 30.6 33265-46480 41.7 2013 5672-31982 15.1 40937-85904 32.3 39042-88940 30.5 33030-48148 40.7 2014 5692-36743 13.4 37421-78514 32.3 38370-89880 29.9 37169-53870 40.8 SUM 29267-168880 14.8 205496-421018 32.8 193971-439414 30.6 168734-238137 41.5

Since there are three offensive players in the same spot for every free throw, one might think of all the shots listed that free throws could be immune to the dominant philosophy of defending transition. While the drop in second chances that occur on free-throw misses isn’t going to be a premium source of clickbait, it does have ramifications for a certain strategy I’ll detail in the future.

It’s not surprising that shots recorded by the scorer’s table as layups, dunks, or tips are more likely to be rebounded by the offense than two-point jumpers which themselves are more likely to be rebounded by the offense than three-pointers.

There may be a large gradient across the domain of two-point jumpers, though. Based on the layup and three-point numbers, it figures that a seven-foot jumper has a higher offensive rebounding percentage than a 15-foot jumper. Based on Kirk Goldsberry’s work using the NBA’s SportVu data, it’s possible that the latter is rebounded by the offense less often than a typical three-pointer.

3. Offensive rebounds are more likely on blocked shots than shots that get to the rim.

While I’m in the mood for monospaced fonts, let’s continue to break down the offensive rebounding data further for reference purposes if nothing else.

It may not be surprising that shots that make it to the rim are less likely to be rebounded by the defense. Blocked shots that remain in play are basically loose balls and I don’t know of anyone that practices rebounding blocked shots. Here’s a breakdown of the numbers after separating shots that are blocked from shots that aren’t.

NON-BLOCKED SHOTS ONLY

2-point jumpers 3-pointers Layups

Year OR-DR OR% OR-DR OR% OR-DR OR%

2010 37065-77659 32.3 38712-85511 31.2 23981-34383 41.1

2011 36161-77830 31.7 38036-86083 30.6 23610-33718 41.2

2012 35142-76351 31.5 37868-86197 30.5 24050-35128 40.6

2013 35041-77767 31.1 38322-87933 30.4 23746-36339 39.5

2014 31730-70843 30.9 37717-88936 29.8 26610-40490 39.7

SUM 175139-380450 31.5 190655-434660 30.5 121997-180058 40.4

BLOCKED SHOTS ONLY

2-point jumpers 3-pointers Layups

Year OR-DR OR% OR-DR OR% OR-DR OR%

2010 6580-8484 43.7 624-913 40.6 8880-10764 45.2

2011 6269-8385 42.8 681-941 42.0 8799-10774 45.0

2012 5921-7891 42.9 638-949 40.2 9215-11352 44.8

2013 5896-8137 42.0 720-1007 41.7 9284-11809 44.0

2014 5691-7671 42.6 653-944 40.9 10559-13380 44.1

SUM 23933-31877 42.9 2730-3908 41.1 38086-47448 44.5

Many of these offensive rebounds are the result of shots being blocked out of bounds, which don’t fall into the loose ball category. We can get a handle on the OR% for blocked shots kept in play by excluding rebounds labeled as team rebounds, since the vast majority of these happen when the ball goes out of bounds. This is where things get interesting.

4. Shots blocked in play are about as likely to be rebounded by the defense as shots that make it to the rim.

Perhaps this isn’t too surprising, either, but blocked shots seem like loose balls, and since rebounding technique probably goes out the window in these cases, one might figure the offense has some advantage over the typical shot. But there’s only a very small lean to the offense on blocks of two-point jumpers and three-pointers compared to their non-blocked counterparts. And blocked layups that stay in play are significantly more likely to be rebounded by the defense than layups that get to the rim.

BLOCKED SHOTS (IN PLAY) ONLY

2-point jumpers 3-pointers Layups

Year OR-DR OR% OR-DR OR% OR-DR OR%

2010 3891-7837 33.2 381-851 30.9 4827-9936 32.7

2011 3765-7849 32.4 440-873 33.5 5011-10054 33.3

2012 3548-7408 32.4 401-888 31.1 5155-10593 32.7

2013 3516-7603 31.6 444-926 32.4 5060-11037 31.4

2014 3365-7213 31.8 391-883 30.7 5848-12459 31.9

SUM 18085-37910 32.3 2057-4421 31.8 25901-54079 32.4

NON-BLOCKED SHOTS ONLY

2-point jumpers 3-pointers Layups

SUM 175139-380450 31.5 190655-434660 30.5 121997-180058 40.4

If you consider the traditional ball-you-man mentality, defenders would be in better position to recover a blocked shot. This is especially true in the case of layups where blocks result in rebounds that are significantly farther away from the rim than a non-block.

The best point to take away is that if shot blockers keep their swats in play, their teammates have about the same chance of securing the ball than if the ball got to the rim. Or in the case of layups – where most blocks occur – a much better chance. Keeping blocks in play is surely a skill to some extent and it’s an important one for a rim protector.

5. Offensive rebounding is partly about effort.

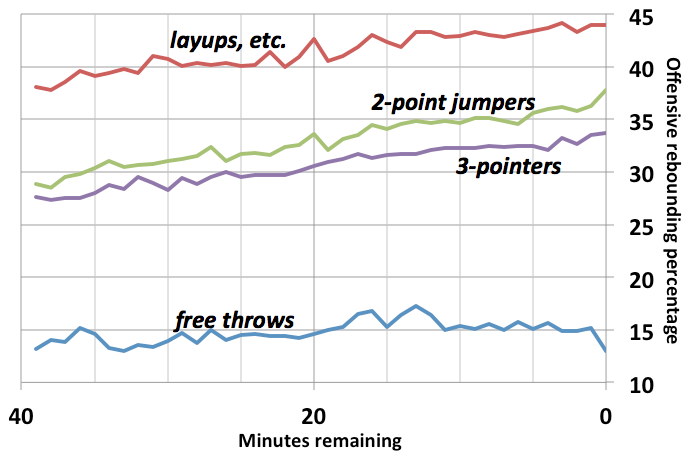

You’ll occasionally hear a commentator claim that rebounding is about effort. I would propose that rebounding is mostly about size and athleticism, but no doubt there’s a component to rebounding that involves effort and anticipation. And more effort is made the deeper into the game we get. If you’ve made it this far, you deserve a chart.

Basically, offensive rebounding percentage increases as a function of time elapsed. One might assume that early in the game, players are cautious about picking up an early foul and take fewer chances trying to grab an offensive rebound. Later in the game, these concerns diminish and more effort is made trying to rebound a miss.

Note that in the final minute, OR% on free throws drops dramatically. This figures to be the result of the leading team taking most of these shots and having little motivation to risk a foul on trying to grab an offensive board. For the other shots in the final minute, the losing team is responsible for the majority of the attempts and it’s more likely to sell out for second chances in an attempt catch up. Thus the final minute has the highest offensive rebounding percentage for non-layups.

So that’s a bunch of stuff on offensive rebounds. Maybe a few things you wanted to know and some you didn’t.